Decelerating inflation is bringing some crumbs of comfort to households whose living standards have been ravaged by rising costs. A year ago, when inflation had accelerated to 9%, the April uprating of Universal Credit was only 3.1%, leaving recipients 6% worse off over the year (in addition to the removal of the temporary £20 a week pandemic uplift). But this year, the inflation rate to April has fallen to 8.7%, so with a 10.1% uprating, UC has risen 1.4% in real terms. In both cases this is because of the lag caused by April upratings being based on the previous September’s inflation rate. When inflation is accelerating, real benefits fall; when it is decelerating, they rise. With inflation projected to keep on falling, a further (and probably much larger) gain of this kind is likely a year from now.

Until 2022, having these lagged upratings made relatively little difference: with inflation low, the April rate had only been more than two percentage points higher than the September rate once in the previous 30 years. And over the long term, inflation-linked benefits always ‘catch up’ with rising prices, as the October to April increases feed into the following year’s uprating. But there are several reasons to remain concerned about the effect of the lag today.

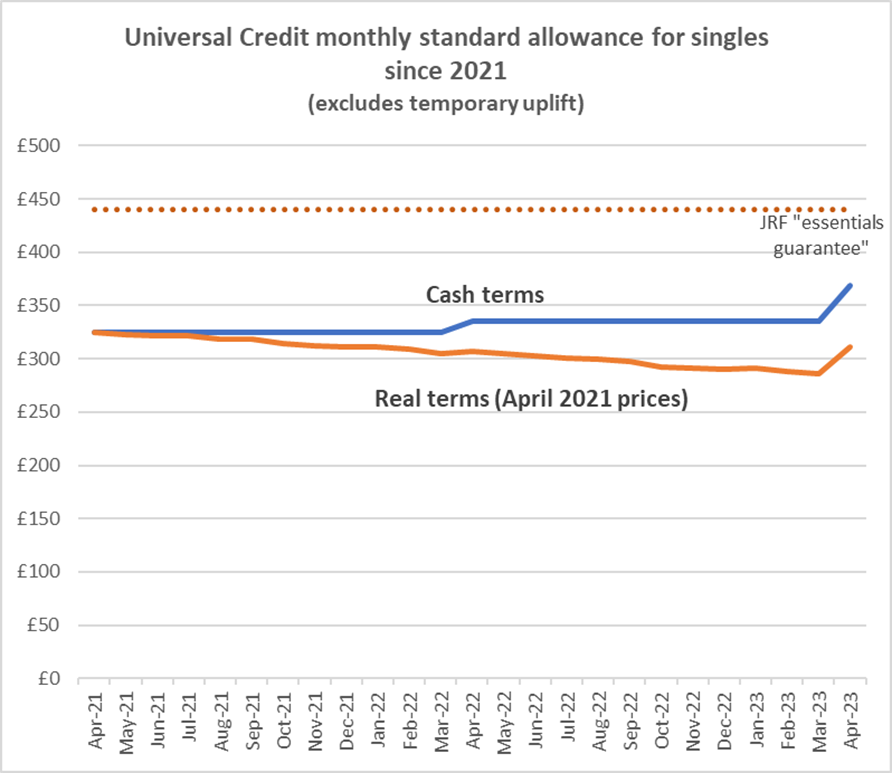

Most obviously, claimants have just had to cope with a year with benefits significantly lower in real terms than previously, and the gain in the present financial year is much lower (1.4%) than the previous year’s loss (5.9%). In 2024, there should be larger gains, but for someone struggling on a very low income now, knowing these are on the way is not much solace. This graph shows that in real terms, benefit incomes still remain lower than in 2021, by £14 a month for a single. For couple with two children, the real-terms loss has been £49 a month, nearly £600 a year.

This is before ad hoc additional payments, such as the living costs support of £900 a year that UC claimants receive in 2023/24. But don’t forget that in April 2021, they were getting more than that from the £20 a week (£1040 a year) temporary UC uplift, now discontinued. Moreover, these ad hoc payments are poor substitutes for decent benefit rates in helping the worst-off: they are not weighted to household size, and create big uncertainties about future income among households who do not have the capacity to absorb large income fluctuations.

And the graph shows that families depending on Universal credit can take little comfort from the 1.4% real increase they’ve seen in their benefits in the past year, coming after two years of declining real benefit levels. Most important of all, the starting point was at a historically low level by any measure, and clearly insufficient to cover the most frugal existence. Benefits for working age adults without children are now only a quarter of what families need for a decent living standard, and 30 per cent lower even than what the Joseph Rowntree Foundation estimates as being needed for an “essentials guarantee”, based on what worse-off families actually spend.

There is growing consensus around the urgent need for a generalised increase in these alarmingly low levels of support, leading to powerful initiatives such as the Scottish Minimum Income Guarantee project supported by the Financial Fairness Trust, and backed by the Scottish Government. And even the cross-party House of Commons Select Committee on Work and Pensions, which has previously been wary of weighing in on such a political issue, is now looking at the basis for setting benefit levels.

And as well as the levels of this support, the way in which it arrives is crucial – in particular in terms of its predictability and timeliness. In rethinking how benefits can provide a rock of guaranteed minimum income in unstable times, they need to track changing prices as closely as possible. Universal Credit’s use of electronic rather than paper-based delivery systems gives the potential for a new start here. At the very least, we can hope that unnecessary time lags will become a 20th century relic.